The Straight Line to Humanity: Debunking the Outdated Model of Human Evolution

For much of the early 20th century, the prevailing image of human evolution was a linear progression, a straight line from ape-like ancestors to modern Homo sapiens. This perspective, known as phyletic gradualism, was heavily influenced by the Modern Synthesis of the 1940s, a period that saw the unification of Darwinian evolution with Mendelian genetics. While the Modern Synthesis provided a robust framework for understanding evolutionary processes, it also inadvertently fostered a simplified view of human origins, one that depicted a steady, predictable march toward anatomical modernity.

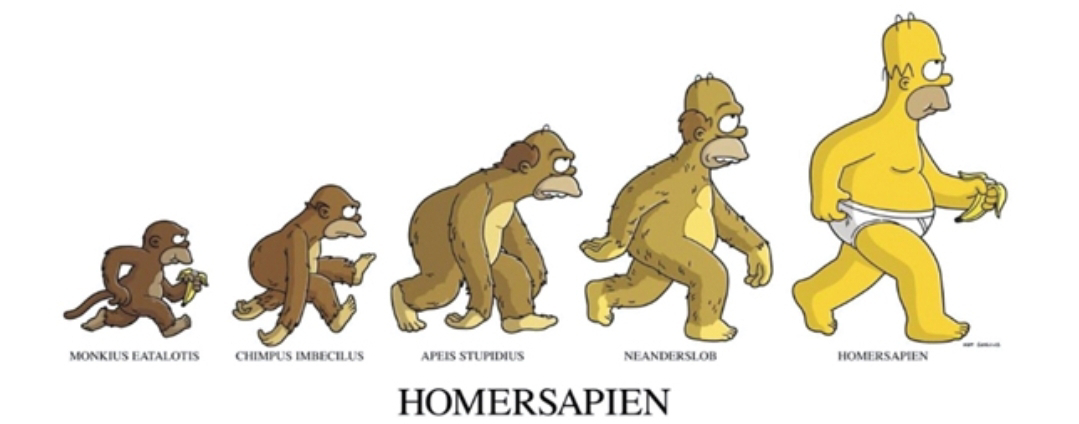

This linear model, often visualized as a single line of hominids gradually standing taller and developing larger brains, was reflected in the hominid phylogenies (evolutionary trees) of the time. These phylogenies often featured a single lineage, with each species replacing the previous one in a sequential manner. This simplistic representation failed to capture the true complexity of human evolution, a story characterized by branching lineages, dead ends, and periods of coexistence between different hominid species.

Several factors contributed to the popularity of the linear model. First, the fossil record in the early 20th century was relatively sparse. With limited fossil evidence, it was easier to construct a straightforward narrative of human evolution. Second, the Modern Synthesis emphasized gradual change over long periods, leading to a focus on anagenesis, the transformation of a single lineage over time. This emphasis on gradualism downplayed the role of cladogenesis, the splitting of lineages, which is crucial for understanding the bushy nature of the hominid family tree.

Furthermore, the socio-political context of the time may have also played a role. The linear model, with its implication of progress and directionality, resonated with a world grappling with industrialization, colonialism, and the rise of social Darwinism. The idea of a predetermined evolutionary trajectory, culminating in modern humans, could be easily misused to justify social hierarchies and discriminatory practices.

However, starting in the 1970s, new fossil discoveries and advances in dating techniques began to challenge the linear model. The discovery of multiple hominid species living contemporaneously, such as Homo habilis and Homo erectus, shattered the notion of a single, sequential lineage. The fossil record was revealing a more complex picture, one with multiple branches, dead ends, and instances of convergent evolution.

The development of cladistics, a method of classifying organisms based on shared derived characteristics, also contributed to a shift in perspective. Cladistics provided a more rigorous framework for reconstructing evolutionary relationships, allowing scientists to identify branching patterns and infer ancestral relationships with greater accuracy.

By the end of the 20th century, the linear model had largely been replaced by a more nuanced understanding of human evolution. The hominid family tree was no longer depicted as a straight line but as a branching bush, reflecting the diversity and complexity of our evolutionary history. This shift in perspective was accompanied by a growing recognition of the role of cladogenesis, punctuated equilibrium (periods of rapid change followed by stasis), and other evolutionary processes that were previously downplayed.

The move away from the linear model has had profound implications for our understanding of human origins. It has highlighted the importance of considering the ecological, environmental, and social factors that shaped human evolution. It has also emphasized the dynamic nature of the evolutionary process, with its potential for both gradual change and rapid diversification.

In conclusion, the linear model of human evolution, prevalent in the first half of the 20th century, was a product of its time, influenced by the Modern Synthesis, limited fossil evidence, and perhaps even socio-political biases. However, new discoveries and advances in methodology have led to a more accurate and nuanced understanding of our evolutionary history. The hominid family tree is not a straight line but a branching bush, reflecting the complex interplay of factors that shaped our species. This shift in perspective has enriched our understanding of human origins and continues to guide research in paleoanthropology today.

Comments

Post a Comment